A wee bit back, reader Brian Proulx of Alexandria related a story his dad had told him about agents of the British Crown and the Royal Navy scouring Glengarry in the 1800s for hardwood ashes. With the help of kind readers who answered my call for assistance, I think I found out why the ashes were being sought. And, in doing so, I stumbled across another icky manufacturing process: the making of gunpowder in olden times. Like its cousins — the stuffing of sausages and the passing of laws — it’s best to be spared the details, if one can. But we can’t. Not if we want to get to the root of Brian’s quest.

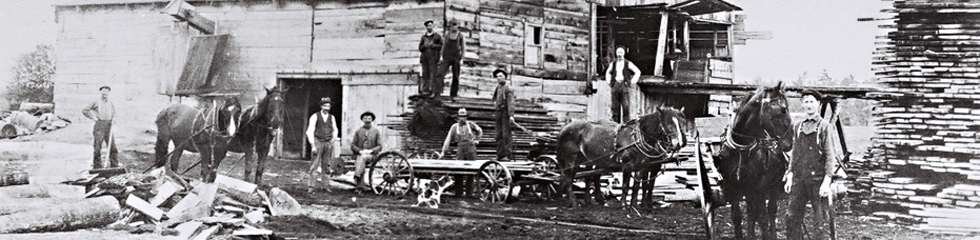

In the early 1800s, the main focus of pioneers in Kenyon and neighbouring townships was the clearing of land for farming. Being Glengarry, naturally this involved moving a whole lot of rocks. But it also meant felling a whack of trees. Far more than the settlers needed for firewood or lumber to build cabins, outbuildings and fences. The excess timber was usually burned off, producing the settlers’ first cash crop: ashes.

Huge iron pots bubbling on an open fire were a common site on early farmsteads as the ashes from countless clearance bonfires were soaked in hot water to produce lye, which the settlers mixed with fat to make homemade soap. But there’s only so much soap a family can use. So the excess lye solution was boiled down to produce ‘pot ash’ which, in turn, could be sold to a nearby ashery. There the carbon impurities would be removed and the finished product — white pearl ash — would be sold to manufacturers in Great Britain for the production of glass and ceramic wares. Asheries were often one of the first commercial enterprises to spring up in the embryonic hamlets of Glengarry. They were a welcome source of cash… coin of the realm the pioneers could use for store bought’n goods like sugar and tea.

But this still leaves us with the agents of the Crown trekking hither and yon schlepping empty barrels and looking for the milky white ash that results when hard maple is consumed by flame. As near as I can figure, they were trying to satisfy the British Empire’s voracious appetite for gunpowder, the making of which requires top-notch hardwood ash. When burned, hardwood species like maple, oak and elm produce ashes that contain much higher levels of potassium carbonate and potassium hydroxide than the ash of softwood trees. I surmise that these prized ashes were shipped back to England to be turned into the premium-grade liquid lye needed in the production of black powder for the Empire’s smoothbore cannons, muskets and pistols.

Now we get to the messy bit. In the centuries before it was discovered as a mineable mineral in India, the key ingredient of gunpowder — saltpeter (aka: potassium nitrate or KNO3) — had to be extracted using a labourious and odiferous, process that took months. First, you needed a large shallow mixing bed with a waterproof liner. A hole in the ground lined with clay and protected from the rains by a roof worked perfectly. Then you filled it with animal dung, straw, a pinch of wood ash and, last but not least, lots and lots of human urine.

In 17th century England, government officials had the authority to enter any property they chose in search of urine, including houses of worship. At the time, many English churches had rush-covered, packed-earth floors. As Michael Miner wrote In a recent Chicago Reader post, “In 1638, saltpeter men, as they were known, had sought permission to extend their activities to the floors of churches, because women pisse in their seats which causes excellent saltpeter.” I’m guessing the fair ladies were forced to endure some marathon-length sermons.

After months of turning over the heady mixture, it was finally removed from the pit, placed in wooden barrels and water was poured through it to dissolve the nitrate salts. The rinse water — called ley — was retained and mixed with fresh lye made from the fine white ash of the hard maple trees of Glengarry and elsewhere in North America. When a whitish cloud appeared, the mixture was allowed to evaporate. And voila, a fresh batch of saltpeter was ready to be mixed in the correct proportions with powdered charcoal and sulfur to produce, at long last, gunpowder.

I’d like to thank my son Brendan and readers Brian Proulx, John Downing and Richard Burton for their invaluable assistance with this item.

Electric erratum

In a column from early December 2020, I commented on a 1920 front-page Glengarry Newsarticle on a 26,000-volt high-tension transmission line being built from Cornwall to Alexandria, stating that its completion “would finally bring electricity to Alexandria.” This, dear reader, was incorrect. It would appear I was off by 24 years. As my friend Dane Lanken kindly pointed out: “Alexandria got electricity in 1896 when the Delisle River north of town was damned and a generator installed. Power was supplied for a certain number of hours per day. I believe that was the situation for 24 years, until 1920 when lines were put in place to bring hydro power in from away… The Delisle River dam fell into disuse, though it’s still there today, as is the name of the road it’s on, Power Dam Road.” Thank you Dane, for keeping me honest.

Imitation = flattery

Bringing up the rear of this week’s column is a good news story from the Glengarry Pioneer Museum. At last week’s virtual Executive Committee meeting, curator Jennifer Black reported that she had received a call from the curator of the Cornwall Community Museum. The museum wanted to apply for Ontario’s Community Museum Operating Grant (CMOG) and was in the process of ensuring its procedures and policies were in line with the minimum operational standards required to qualify for funding under the program. These standards cover everything from Governance, Finance and Collections, to Exhibitions, Physical Plant and Human Resources. Out of interest, I visited the CMOG web site and drilled down into some of the standards, which I discovered are very detailed indeed. They even specify the acceptable light levels for different artefact categories. For example, 50 lux for highly light sensitive materials like dyed textiles and 300 lux for materials that are not light sensitive, such as stone and ceramics.

Jennifer was tickled pink when she learned from the caller that Elka Weinstein, the Museum and Heritage Programs Advisor with Ontario’s Ministry of Heritage, Sport, Tourism and Culture, had suggested that, rather than reinventing the wheel, Cornwall ask the Glengarry Pioneer Museum for permission to use their policy document as a starting point. Ms. Weinstein told the Cornwall museum that the GPM’s policies are “a perfect example for museums of our size in this region.” Which is high praise indeed.

And, to top things off, this request was followed by a second one. This time from the Ontario Historical Society. Jennifer reported that the OHS contacted the museum to inquire about borrowing the Glengarry Pioneer Museum’s bylaws and policies. The society is helping with the incorporation of a new museum in Hamilton and hoped to use what the Glengarry museum has developed as a foundation for its governance structure.

“Both these requests are heart-warming validation for a small community-run museum like the one in Dunvegan,” Matt Williams, the Executive Committee Chair told me in an email. “It’s a testament to the outstanding work done by Karen Davidson Wood in drafting the original set of policies in 2013. Her expertise helped establish the museum as an organization worthy of imitation.”

And Matt is right. Karen and the other members of the committee that took on the task of aligning the Glengarry Pioneer Museum’s policies with Ontario’s standards so many years ago are to be complimented for doing such a fine job.

-30-